Greeting and Information

Welcome to the online trading educational page and we want to share with you about financial trading and experiences such as CFD and Stocks, Currencies, Commodities, Oil, and Cryptos in 2021. And we are proud to say that nowadays in the 21st century the online financial trading is going to top fast income from stay at home time.

Our Aim is from the Online Financial Trading to become a successful trader for Beginners and Experts and can make more income. We provide forex trading information, free trading strategies, and courses to help the traders achieve their goals. Practice on the free virtual demo trading accounts with a strategy, execute trade orders, protect yourself against the risk of loss, and lock in your gains. But you should need to know what you’re doing that involved financial risk.

Information on the site is being presented from third parties’ sources and without consideration of the investment objectives such as risk tolerance, or the online financial circumstances of any specific investor and might not be suitable for all investors.

TRADE THE ONLINE FINANCIAL MARKETS

Top Trading Conditions

- Ultra-fast execution from 0.1s

- Social and Copy Trading Platform

- All trading strategies allowed

Top Profitable Broker

- Easy and Profitable

- Low spreads from 0.01 pip

- Risk-free Demo Account

Top Forex Broker

- Over 2M Account Registered

- 30% Deposit Bonus To Non EU Traders

- MT4, MT5 and Web Trader Platforms

Financial Markets

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Are Financial Markets?

- Understanding Financial Markets

- Types of Financial Markets

- Forex Market

- Cash Market

- Commodity Market

- Derivative Market

- Capital Markets

- Equity Capital Market (ECM)

- Bond Market

- Over-the-Counter Market

- Cryptocurrencies Market

- Examples of Financial Markets

- Financial Markets FAQs

What Are Financial Markets?

Financial markets refer broadly to any marketplace where the trading of securities occurs, including the stock market, bond market, forex market, and derivatives market, among others. Financial markets are vital to the smooth operation of capitalist economies.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Financial markets refer broadly to any marketplace where the trading of securities occurs.

- There are many kinds of financial markets, including (but not limited to) forex, money, stock, and bond markets.

- These markets may include assets or securities that are either listed on regulated exchanges or else trade over-the-counter (OTC).

- Financial markets trade in all types of securities and are critical to the smooth operation of a capitalist society.

- When financial markets fail, economic disruption including recession and unemployment can result.

Understanding the Financial Markets

Financial markets are a vital role in facilitating the smooth operation of capitalist economies by allocating resources and creating liquidity for businesses and entrepreneurs. The markets make it easy for buyers and sellers to trade their financial holdings. Financial markets create securities products that provide a return for those who have excess funds (Investors/lenders) and make these funds available to those who need additional money (borrowers).

The stock market is just one type of financial market. Financial markets are made by buying and selling numerous types of financial instruments including equities, bonds, currencies, and derivatives. Financial markets rely heavily on informational transparency to ensure that the markets set prices that are efficient and appropriate. The market prices of securities may not be indicative of their intrinsic value because of macroeconomic forces like taxes.

Some financial markets are small with little activity, and others, like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), trade trillions of dollars of securities daily. The equities (stock) market is a financial market that enables investors to buy and sell shares of publicly traded companies. The primary stock market is where new issues of stocks, called initial public offerings (IPOs), are sold. Any subsequent trading of stocks occurs in the secondary market, where investors buy and sell securities that they already own.

Prices of securities traded in the financial markets may not necessarily reflect their true intrinsic value.

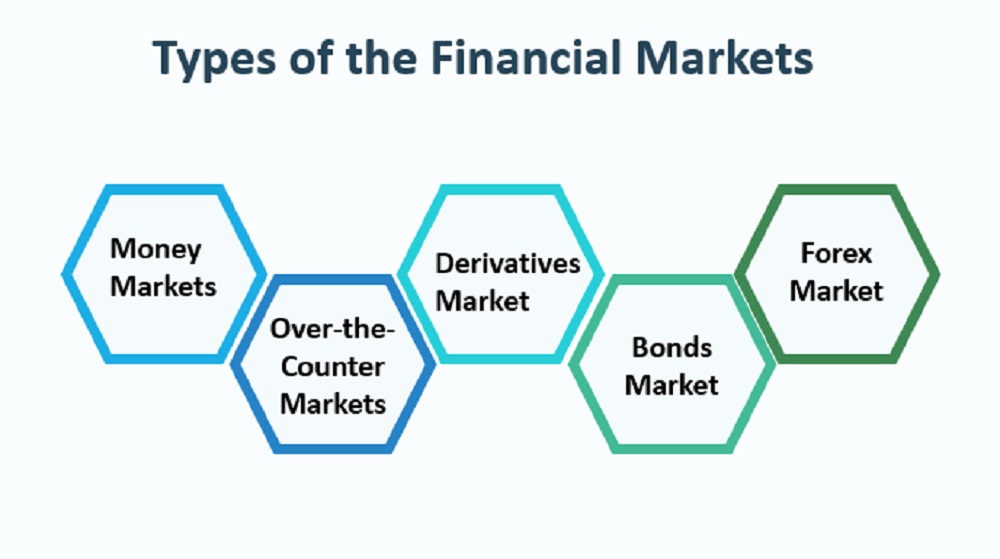

Types of Financial Markets

Stock Markets

Perhaps the most ubiquitous of financial markets are stock markets. These are venues where companies list their shares and they are bought and sold by traders and investors. Stock markets, or equities markets, are used by companies to raise capital via an initial public offering (IPO), with shares subsequently traded among various buyers and sellers in what is known as a secondary market.

Stocks may be traded on listed exchanges, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or Nasdaq, or else over-the-counter (OTC). Most trading in stocks is done via regulated exchanges, and these play an important role in the economy as both a gauge of the overall health in the economy as well as providing capital gains and dividend income to investors, including those with retirement accounts such as IRAs and 401(k) plans.

Typical participants in a stock market include (both retail and institutional) investors and traders, as well as market makers (MMs) and specialists who maintain liquidity and provide two-sided markets. Brokers are third parties that facilitate trades between buyers and sellers but who do not take an actual position in a stock.

Over-the-Counter Markets

An over-the-counter (OTC) market is a decentralized market—meaning it does not have physical locations, and trading is conducted electronically—in which market participants trade securities directly between two parties without a broker. While OTC markets may handle trading in certain stocks (e.g., smaller or riskier companies that do not meet the listing criteria of exchanges), most stock trading is done via exchanges. Certain derivatives markets, however, are exclusively OTC, and so make up an important segment of the financial markets. Broadly speaking, OTC markets and the transactions that occur on them are far less regulated, less liquid, and more opaque.

Bond Markets

A bond is a security in which an investor loans money for a defined period at a pre-established interest rate. You may think of a bond as an agreement between the lender and borrower that contains the details of the loan and its payments. Bonds are issued by corporations as well as by municipalities, states, and sovereign governments to finance projects and operations. The bond market sells securities such as notes and bills issued by the United States Treasury, for example. The bond market also is called the debt, credit, or fixed-income market.

Money Markets

Typically, the money markets trade in products with highly liquid short-term maturities (of less than one year) and are characterized by a high degree of safety and a relatively low return in interest. At the wholesale level, the money markets involve large-volume trades between institutions and traders. At the retail level, they include money market mutual funds bought by individual investors and money market accounts opened by bank customers. Individuals may also invest in the money markets by buying short-term certificates of deposit (CDs), municipal notes, or U.S. Treasury bills, among other examples.

Derivatives Markets

A derivative is a contract between two or more parties whose value is based on an agreed-upon underlying financial asset (like a security) or set of assets (like an index). Derivatives are secondary securities whose value is solely derived from the value of the primary security that they are linked to. In and of itself a derivative is worthless. Rather than trading stocks directly, a derivatives market trades in futures and options contracts, and other advanced financial products, that derive their value from underlying instruments like bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates, market indexes, and stocks.

Futures markets are where futures contracts are listed and traded. Unlike forwards, which trade OTC, futures markets utilize standardized contract specifications, are well-regulated, and utilize clearinghouses to settle and confirm trades. Options markets, such as the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), similarly list and regulate options contracts. Both futures and options exchanges may list contracts on various asset classes, such as equities, fixed-income securities, commodities, and so on.

Forex Market

The forex (foreign exchange) market is the market in which participants can buy, sell, hedge, and speculate on the exchange rates between currency pairs. The forex market is the most liquid market in the world, as cash is the most liquid of assets. The currency market handles more than $5 trillion in daily transactions, which is more than the futures and equity markets combined. As with the OTC markets, the forex market is also decentralized and consists of a global network of computers and brokers from around the world. The forex market is made up of banks, commercial companies, central banks, investment management firms, hedge funds, and retail forex brokers and investors.

Commodities Markets

Commodities markets are venues where producers and consumers meet to exchange physical commodities such as agricultural products (e.g., corn, livestock, soybeans), energy products (oil, gas, carbon credits), precious metals (gold, silver, platinum), or “soft” commodities (such as cotton, coffee, and sugar). These are known as spot commodity markets, where physical goods are exchanged for money.

The bulk of trading in these commodities, however, takes place on derivatives markets that utilize spot commodities as the underlying assets. Forwards, futures, and options on commodities are exchanged both OTC and on listed exchanges around the world such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) and the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE).

Cryptocurrency Markets

The past several years have seen the introduction and rise of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, decentralized digital assets that are based on blockchain technology. Today, hundreds of cryptocurrency tokens are available and trade globally across a patchwork of independent online crypto exchanges. These exchanges host digital wallets for traders to swap one cryptocurrency for another, or for fiat monies such as dollars or euros.

Because the majority of crypto exchanges are centralized platforms, users are susceptible to hacks or fraud. Decentralized exchanges are also available that operate without any central authority. These exchanges allow direct peer-to-peer (P2P) trading of digital currencies without the need for an actual exchange authority to facilitate the transactions. Futures and options trading are also available on major cryptocurrencies.

Examples of Financial Markets

The above sections make clear that the “financial markets” are broad in scope and scale. To give two more concrete examples, we will consider the role of stock markets in bringing a company to IPO, and the role of the OTC derivatives market in the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Stock Markets and IPOs

When a company establishes itself, it will need access to capital from investors. As the company grows it often finds itself in need of access to much larger amounts of capital than it can get from ongoing operations or a traditional bank loan. Firms can raise this size of capital by selling shares to the public through an initial public offering (IPO). This changes the status of the company from a “private” firm whose shares are held by a few shareholders to a publicly-traded company whose shares will be subsequently held by numerous members of the general public.

The IPO also offers early investors in the company an opportunity to cash out part of their stake, often reaping very handsome rewards in the process. Initially, the price of the IPO is usually set by the underwriters through their pre-marketing process.

Once the company’s shares are listed on a stock exchange and trading in it commences, the price of these shares will fluctuate as investors and traders assess and reassess their intrinsic value and the supply and demand for those shares at any moment in time.

OTC Derivative Markets and the 2008 Financial Crisis: MBS and CDOs

While the 2008-09 financial crisis was caused and made worse by several factors, one factor that has been widely identified is the market for mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These are a type of OTC derivatives where cash flows from individual mortgages are bundled, sliced up, and sold to investors. The crisis was the result of a sequence of events, each with its own trigger and culminating in the near-collapse of the banking system. It has been argued that the seeds of the crisis were sown as far back as the 1970s with the Community Development Act, which required banks to loosen their credit requirements for lower-income consumers, creating a market for subprime mortgages.

The amount of subprime mortgage debt, which was guaranteed by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, continued to expand into the early 2000s, when the Federal Reserve Board began to cut interest rates drastically to avoid a recession. The combination of loose credit requirements and cheap money spurred a housing boom, which drove speculation, pushing up housing prices and creating a real estate bubble. In the meantime, the investment banks, looking for easy profits in the wake of the dotcom bust and the 2001 recession, created a type of MBS called collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) from the mortgages purchased on the secondary market.

Because subprime mortgages were bundled with prime mortgages, there was no way for investors to understand the risks associated with the product. When the market for CDOs began to heat up, the housing bubble that had been building for several years had finally burst. As housing prices fell, subprime borrowers began to default on loans that were worth more than their homes, accelerating the decline in prices.

When investors realized the MBS and CDOs were worthless due to the toxic debt they represented, they attempted to unload the obligations. However, there was no market for the CDOs. The subsequent cascade of subprime lender failures created liquidity contagion that reached the upper tiers of the banking system. Two major investment banks, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, collapsed under the weight of their exposure to subprime debt, and more than 450 banks failed over the next five years. Several of the major banks were on the brink of failure and were rescued by a taxpayer-funded bailout.

Financial Markets FAQs

What Are the Different Types of Financial Markets?

Some examples of financial markets and their roles include the stock market, the bond market, forex, commodities, and the real estate market, among several others. Financial markets can also be broken down into capital markets, money markets, primary vs. secondary markets, and listed vs. OTC markets.

How Do Financial Markets Work?

Despite covering many different asset classes and having various structures and regulations, all financial markets work essentially by bringing together buyers and sellers in some asset or contract and allowing them to trade with one another. This is often done through an auction or price-discovery mechanism.

What Are the Main Functions of Financial Markets?

Financial markets exist for several reasons, but the most fundamental function is to allow for the efficient allocation of capital and assets in a financial economy. By allowing a free market for the flow of capital, financial obligations, and money the financial markets make the global economy run more smoothly while also allowing investors to participate in capital gains over time.

Why Are Financial Markets Important?

Without financial markets, capital could not be allocated efficiently, and economic activity such as commerce & trade, investment, and growth opportunities would be greatly diminished.

Who Are the Main Participants in Financial Markets?

Firms use stock and bond markets to raise capital from investors; speculators look to various asset classes to make directional bets on future prices; hedgers use derivatives markets to mitigate various risks, and arbitrageurs seek to take advantage of mispricing or anomalies observed across various markets. Brokers often act as mediators that bring buyers and sellers together, earning a commission or fee for their services.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Forex Market

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is the Forex Market?

- Understanding the Forex Market

- History of the Forex Market

- Type of Forex Markets

- Big Players in the Forex Market

- Pros and Cons of Forex Trading

- Forex Market FAQs

- The Bottom Line

What Is the Forex Market?

The forex market allows participants, such as banks and individuals, to buy, sell or exchange currencies for both hedging and speculative purposes. The foreign exchange (forex) market is the largest financial market in the world and is made up of banks, commercial companies, central banks, investment management firms, hedge funds, retail forex brokers, and investors.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The forex market allows participants, including banks, funds, and individuals to buy, sell or exchange currencies for both hedging and speculative purposes.

- The forex market operates 24 hours, 5.5 days a week, and is responsible for trillions of dollars in daily trading activity.

- Forex trading can provide high returns but also brings high risk.

- The forex market is made up of two levels: the interbank market and the over-the-counter (OTC) market.

- Many forex accounts can be opened with as little as $100.

Understanding the Forex Market

The forex market is not dominated by a single market exchange, but a global network of computers and brokers from around the world. Forex brokers act as market makers as well and may post bid and ask prices for a currency pair that differs from the most competitive bid in the market.

The forex market is made up of two levels—the interbank market and the over-the-counter (OTC) market. The interbank market is where large banks trade currencies for purposes such as hedging, balance sheet adjustments, and on behalf of clients. The OTC market, on the other hand, is where individuals trade through online platforms and brokers.

Daily Turned Over $6.6 Trillion.

The number of daily forex transactions registered in April 2019, according to the 2019 Triennial Central Bank Survey of FX and OTC derivatives markets.

From Monday morning in Asia to Friday afternoon in New York, the forex market is a 24-hour market, meaning it does not close overnight. The forex market opens from Sunday at 5 p.m. EST to Friday at 4 p.m. EST.

This differs from markets such as equities, bonds, and commodities, which all close for a period of time, generally in the late afternoon EST. However, as with most things, there are exceptions. Some emerging market currencies close for a period of time during the trading day.

History of the Forex Market

Up until World War I, currencies were pegged to precious metals, such as gold and silver. Then, after the Second World War, the system collapsed and was replaced by the Bretton Woods agreement. That agreement resulted in the creation of three international organizations to facilitate economic activity across the globe. They were the following:

- International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD)

The new system also replaced gold with the U.S. dollar as a peg for international currencies. The U.S. government promised to back up dollar supplies with equivalent gold reserves. But the Bretton Woods system became redundant in 1971 when U.S. President Richard Nixon announced a “temporary” suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold.

Currencies are now free to choose their own peg and their value is determined by supply and demand in international markets.

Type of Forex Markets

Three are three key types of forex markets: spot, forward, and futures.

Spot Forex Market

The spot market is the immediate exchange of currency between buyers and sellers at the current exchange rate. The spot market makes up much of the currency trading.

The key participants in the spot market include commercial, investment, and central banks, as well as dealers, brokers, and speculators. Large commercial and investment banks make up a major portion of spot trades, trading not only for themselves but also for their customers.

Forward Forex Market

In the forward markets, two parties agree to trade a currency for a set price and quantity at some future date. No money exchanges hands when the deal is made. The two parties can be companies, individuals, governments, or the like. Forward markets are useful for hedging.

On the downside, forward markets lack centralized trading and are relatively illiquid (since there are just the two parties). As well, there is counter-party risk, which is that the other part will default.

Futures Forex Market

Future markets are similar to forward markets in terms of basic function. However, the big difference is that future markets use centralized exchanges. Thanks to centralized exchanges, there are no counter-party risks for either party. This helps ensure future markets are highly liquid, especially compared to forward markets.

Big Players in the Forex Market

The U.S. dollar is by far the most-traded currency. The second is the euro and the third is the Japanese yen. JPMorgan Chase is the largest trader in the forex market. Chase has 10.8% of the global forex market share. They have been the market leader for three years now. UBS is in second, with 8.1% of the market share. XTX Markets, Deutsche Bank, and Citigroup made up the remaining places in the top five.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Forex Trading

Forex markets have key advantages, but this type of trading doesn’t come without disadvantages.

Pros

- Lots of flexibility, trading almost 24/7

- Plenty of trading options

- Low transaction costs

Cons

- Lack of regulation increases counterparty risk

- High leverage amounts allowed

- Operational risk

Advantages

One of the biggest advantages of forex trading is the lack of restrictions and inherent flexibility. There’s a very large amount of trading volume and markets are open almost 24/7. With that, people who work nine-to-five jobs can also partake in trading at night or on the weekends (unlike the stock market).

There’s a large amount of optionality when it comes to available trading options. There are hundreds of currency pairs, and there are various types of agreements, such as a future or spot agreement. The costs for transactions are generally very low versus other markets and the allowed leverage is among the highest of all financial markets, which can magnify gains (as well as losses).

Disadvantages

With forex markets, there are leverage risks—the same leverage that offers advantages. Forex trading allows for large amounts of leverage. The leverage allowed is 20-30 times and can offer outsized returns, but can also mean large losses quickly.

Although the fact that it operates nearly 24 hours a day can be a positive for some, it also means that some traders will have to use algorithms or trading programs to protect their investments while they are away. This adds to operational risks and can increase costs.

The other major disadvantage is counterparty risk, where regulating Forex markets can be difficult, given it’s an international market that trades almost constantly. There is no central exchange that guarantees a trade, which means there could be default risk.

Forex Market FAQs

What Exactly Is Forex Trading?

Forex trading is the exchange of one currency for another. Forex trading is the trading of currency pairs—buying one currency while at the same time selling another.

Can You Get Rich by Trading Forex?

Forex trading can make you rich, but it’ll likely require deep pockets to do so. That is, hedge funds often have the skills and available funds to make forex trading highly profitable. However, for individual and retail investors, forex trading can be profitable but it’s also very risky.

How Do I Start Trading Forex?

To get started in forex trading, the first step is to learn about forex trading. This includes developing knowledge of the currency markets and specifics of forex trading. It also takes a brokerage account set up for forex trading. One of the more important things from there is setting up a trading strategy, which includes the amount of money you’re willing to risk.

How Much Do You Need to Start Trading Forex?

In most cases, you can open and trade via forex account for as little as $100. Of course, the higher the amount you can invest the greater the potential upside. Many recommend investing at least $1,000 and even $5,000 to properly implement a strategy.

Can I Trade Forex with $100?

It is possible to open and trade forex with just $100—depending on the minimum amount to open a forex account. Some brokers have a minimum deposit requirement of as little as $5 or $10.

The Bottom Line

Forex trading offers several advantages over other markets, such as flexibility with types of contracts and near 24/7 trading. It also allows investors to leverage their trades by 20 to 30 times, which can magnify gains. On the downside, this leverage can also lead to major losses fast.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Cash Market

What Is a Cash Market?

A cash market is a marketplace in which the commodities or securities purchased are paid for and received at the point of sale. For example, a stock exchange is a cash market because investors receive shares immediately in exchange for cash.

Cash markets are also known as spot markets because their transactions are settled “on the spot.” This can be contrasted with derivatives markets such as the futures market, where buyers pay for the right to receive a good, such as a barrel of oil, at a specified date in the future.

The cash market should not be confused with the money market, which involves trading in cash equivalents (i.e. very short-term debt instruments) such as Treasuries and commercial paper.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In a cash (spot) market, purchasers take immediate possession of goods at the point of sale.

- This can be contrasted with derivatives markets, where investors purchase the right to take possession at some future date.

- Stock exchanges are considered cash markets because shares are exchanged for cash at the point of sale.

Understanding Cash Markets

Cash markets can take place either on a regulated exchange, such as a stock market, or in relatively unregulated over-the-counter (OTC) transactions. While regulated exchanges offer institutional protections that can protect against counterparty risks, OTC markets allow the parties involved to customize their contracts. Futures markets are conducted exclusively on exchanges, while forward contracts—typically used in foreign exchange (FX) transactions—are traded on OTC markets.

Sometimes, the line between cash markets and futures markets can get blurred. For example, stock exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) are mostly cash markets, but they also facilitate trading of derivative products which are not settled on the spot. Therefore, depending on the underlying assets being traded, the NYSE and other exchanges can also operate as a futures market.

Whether an investor chooses to transact on a cash market or a futures market will depend on their unique needs. For example, an industrial company that needs oil to fuel its production processes might purchase barrels of oil on a cash market and take physical delivery at the point of sale. By contrast, that same company might wish to hedge against the risk that oil prices will rise in the following years. To do so, it might purchase futures contracts for oil, in which case no physical barrels of oil would exchange hands at the time of sale.

Spot Price

The current price of a financial instrument is called the spot price. It is the price at which an instrument can be sold or bought immediately. Buyers and sellers create the spot price by posting their buy and sell orders. In liquid markets, the spot price may change by the second, as orders get filled and new ones enter the marketplace.

Special Considerations

Many commodities have active cash markets, where physical spot commodities are bought and sold in real-time for cash. FX also has cash currencies markets, where the underlying currencies are physically exchanged following the settlement date. Delivery usually occurs within two days after execution as it generally takes two days to transfer funds between bank accounts. Stock markets can also be thought of as spot markets, with shares of companies changing hands in real-time.

In deciding between cash and derivatives markets, investors will also consider the costs of transacting in each marketplace. For most commodities, the cost of purchasing that commodity in the spot market is lower than its cost in the futures market. This is because there are costs associated with taking physical possession of the commodity, such as storage costs and insurance.

Although a vast amount of transactions take place on cash markets worldwide, a far larger quantity of transactions take place on futures markets. This is mainly due to the various derivative markets, which have become increasingly large and liquid in recent years.

Example of a Cash Market

ABC Foods is a manufacturing company that uses wheat in several of its food products. Rather than cultivating wheat directly, ABC relies on the cash market to provide its wheat supplies. It purchases large amounts of wheat each month from farmers, paying for those goods in cash and stockpiling them in its warehouses.

In addition to its cash-market purchases, ABC also uses forward contracts to secure the right to purchase wheat at predetermined prices in the future. In these situations, ABC does not take possession of the wheat at the point of sale. These transactions take place on an OTC basis between ABC and a specific counterparty, such as a food broker or a specific wheat producer.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Cash Markets

The cash market price is the current quote for immediate purchase, payment, and delivery of a particular commodity. This is incredibly important since prices in derivatives markets, such as for futures and options, will inevitably be based on these values.

Cash markets also tend to be incredibly liquid and active for this reason. Commodity producers and consumers will engage in the spot market and then hedge in the derivatives market.

Pros

- Real-time prices of actual market prices

- Active and liquid markets

- Can take immediate delivery, if desired

Cons

- Taking physical delivery in many cases is not desired

- Not suited for hedging

A disadvantage of the cash market, however, is taking delivery of the physical commodity. If you buy spot pork bellies, you now own some live hogs. While a meat processing plant may desire this, a speculator probably does not.

Another downside is that cash markets cannot be used effectively to hedge against the production or consumption of goods in the future, which is where derivatives markets are better-suited.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Commodity Market

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is a Commodity Market?

- How Commodity Markets Work

- History of Commodity Markets

- Types of Commodity Markets

- Examples of Commodities Markets

- Commodity Market Requirements

- Trading: Commodity Market or Stock

- Commodity Market FAQs

What Is a Commodity Market?

A commodity market is a marketplace for buying, selling, and trading raw materials or primary products.

Commodities are often split into two broad categories: hard and soft commodities. Hard commodities include natural resources that must be mined or extracted—such as gold, rubber, and oil, whereas soft commodities are agricultural products or livestock—such as corn, wheat, coffee, sugar, soybeans, and pork.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- A commodity market involves buying, selling, or trading a raw product, such as oil, gold, or coffee.

- There are hard commodities, which are generally natural resources, and soft commodities, which are livestock or agricultural goods.

- Spot commodities markets involve immediate delivery, while derivatives markets entail delivery in the future.

- Investors can gain exposure to commodities by investing in companies that have exposure to commodities or investing in commodities directly via futures contracts.

- The major U.S. commodity exchanges are ICE Futures U.S. and the CME Group, which holds four major exchanges: The Chicago Board of Trade, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the New York Mercantile Exchange, and the Commodity Exchange, Inc.

How Commodity Markets Work

Commodities markets allow producers and consumers of commodity products to gain access to them in a centralized and liquid marketplace. These market actors can also use commodities derivatives to hedge future consumption or production. Speculators, investors, and arbitrageurs also play an active role in these markets.

Certain commodities, such as precious metals, have been thought of to be a good hedge against inflation, and a broad set of commodities as an alternative asset class can help diversify a portfolio. Because the prices of commodities tend to move in opposition to stocks, some investors also rely on commodities during periods of market volatility.

In the past, commodities trading required significant amounts of time, money, and expertise, and was primarily limited to professional traders. Today, there are more options for participating in the commodity markets.

History of Commodity Markets

Trading commodities goes back to the dawn of human civilization as tribal clans and newly established kingdoms would barter and trade with one another for food, supplies, and other items. Trading commodities indeed predates that of stocks and bonds by many centuries. The rise of empires such as ancient Greece and Rome can be directly linked to their ability to create complex trading systems and facilitate the exchange of commodities across vast swaths via routes like the famous Silk Road that linked Europe to the Far East.

Today, commodities are still exchanged throughout the world and on a massive scale. Things have also become more sophisticated with the advent of exchanges and derivatives markets, Exchanges regulate and standardized commodity trading, allowing for liquid and efficient markets.

Perhaps the most influential modern commodities market is the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), established in 1848, where it originally traded only agricultural commodities such as wheat, corn, and soybeans in order to help farmers and commodity consumers manage risks by removing price uncertainty from those agricultural products.3 Today, it lists options and futures contracts on a wide range of products including gold, silver, U.S. Treasury bonds, and energy products. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Group merged with the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) in 2007, adding interest rates and equity index products to the group’s existing product agricultural offerings.

Some commodities exchanges have merged or gone out of business in recent years. The majority of exchanges carry a few different commodities, although some specialize in a single group. In the U.S., the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) acquired three other commodity exchanges in the mid-2000s. First, CME acquired the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) in 2007 and then in 2008, acquired the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) and the Commodity Exchange, Inc. (COMEX). All four exchanges make up the CME Group. Also in 2007, the New York Board of Trade merged with Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), forming ICE Futures U.S. Each exchange offers a wide range of global benchmarks across major asset classes.

Types of Commodity Markets

Generally speaking, commodities trade either in spot markets or derivatives markets. Spot markets are also referred to as “physical markets” or “cash markets” where buyers and sellers exchange physical commodities for immediate delivery.

Derivatives markets involve forwards, futures, and options. Forwards and futures are derivatives contracts that use the spot market as the underlying asset. These are contracts that give the owner control of the underlying at some point in the future, for a price agreed upon today. Only when the contracts expire would physical delivery of the commodity or other asset take place, and often traders will roll over or close out their contracts in order to avoid making or taking delivery altogether. Forwards and futures are generically the same, except that forwards are customizable and trade over-the-counter (OTC), whereas futures are standardized and traded on exchanges.

Examples of Commodities Markets

The major exchanges in the U.S., which trade commodities, are domiciled in Chicago and New York with several exchanges in other locations within the country. The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was established in Chicago in 1848. Commodities traded on the CBOT include corn, gold, silver, soybeans, wheat, oats, rice, and ethanol. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) trades commodities such as milk, butter, feeder cattle, cattle, pork bellies, lumber, and lean hogs.

The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) trades commodities on its exchange such as oil, gold, silver, copper, aluminum, palladium, platinum, heating oil, propane, and electricity. Formerly known as the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT), ICE Futures U.S. commodities include coffee, cocoa, orange juice, sugar, and ethanol trading on its exchange.

The London Metal Exchange and Tokyo Commodity Exchange are prominent international commodity exchanges.

Commodities are predominantly traded electronically; however, several U.S. exchanges still use the open outcry method. Commodity trading conducted outside the operation of the exchanges is referred to as the over-the-counter (OTC) market.

Commodity Market Regulation

In the U.S., the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) regulates commodity futures and options markets. The CFTC’s objective is to promote competitive, efficient, and transparent markets that help protect consumers from fraud and unscrupulous practices. The CFTC and related regulations were designed to prevent and remove obstructions on interstate commerce in commodities by regulating transactions on commodity exchanges. For example, regulations look to limit, or abolish, short selling and eliminate the possibility of market and price manipulation, such as cornering markets.

The law that established the CFTC has been updated several times since it was created, most notably in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act gave the CFTC authority over the swaps market, which was previously unregulated.

Regulation of commodity markets has continued to remain in the spotlight after ten leading investment banks were caught up in an international precious metals manipulation probe by the CFTC and U.S. Department of Justice in 2015.

Commodity Market Trading vs. Stock Trading

For most individual investors, accessing commodities markets, whether spot or derivatives, is untenable. Direct access to these markets typically requires a special brokerage account and/or certain permissions. Because commodities are considered an alternative asset class, pooled funds that traded commodities futures, such as CTAs, typically only allow accredited investors. Still, ordinary investors can gain indirect access to commodities via the stock market itself. Stocks on mining or materials companies tend to be correlated with commodities prices, and there are various ETFs now that track various commodities or commodities indexes.

Investors looking to diversify their portfolio can look to these ETFs, but for most long-term investors stocks and bonds will make up the core of their holdings. Moreover, because commodity prices tend by more volatile than stocks and bonds, commodities trading is often most suited for those with higher risk tolerance and/or longer time horizon.

Commodity Market FAQs

How Do I Find Out How the Commodity Markets Are Doing Today?

Many online financial portals will provide some indication of certain commodities prices such as gold and crude oil. You can also find prices on the websites of commodity exchanges.

What Do Commodities Traders Do?

Commodities traders buy and sell either physical (spot) commodities or derivatives contracts that use a physical commodity as its underlying. Depending on what type of trader you are, you will use this market for different purposes, for instance, buying or selling a physical product, hedging, speculating, or arbitraging.

Are Commodities a Good Investment?

Like any investment, commodities can be a good investment but also come with risks. An investor needs to understand the markets of the commodity they wish to trade in, for example, the fact that oil prices can fluctuate based on the political climate in the Middle East. The type of investment also matters; ETFs provided more diversification and lower risks where futures are more speculative and the risks are higher because of margin requirements. That being said, commodities are seen as a hedge against inflation, and gold, in particular, can be a hedge against a market downturn.

How Do Commodities Market Work?

For spot markets, buyers and sellers exchange cash for immediate delivery of the physical product. In derivatives markets, buyers and sellers exchange cash for the right to future delivery of that product. Oftentimes, derivatives holders will roll over or close out their positions before delivery can happen. Forwards trade over-the-counter and are customized between counterparties. Futures and options are listed on exchanges and have standardized contracts that are more highly regulated.

What Are Some Examples of Commodities?

There are several commodities available. Energy products include crude oil, natural gas, and gasoline. Precious metals include gold, silver, and platinum. Agricultural products include wheat, corn, soybeans, and livestock. Other commodities you can trade are coffee, sugar, cotton, and frozen orange juice.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Derivative

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is a Derivative?

- Understanding Derivatives

- Special Considerations

- Types of Derivatives

- Advantages and Disadvantages

- What Are Derivatives?

- Examples of Derivatives

- Main Benefits and Risks

What Is a Derivative?

The term derivative refers to a type of financial contract whose value is dependent on an underlying asset, group of assets, or benchmark. A derivative is set between two or more parties that can trade on an exchange or over-the-counter (OTC). These contracts can be used to trade any number of assets and carry their own risks. Prices for derivatives derive from fluctuations in the underlying asset. These financial securities are commonly used to access certain markets and may be traded to hedge against risk.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Derivatives are financial contracts, set between two or more parties, that derive their value from an underlying asset, group of assets, or benchmark.

- A derivative can trade on an exchange or over-the-counter.

- Prices for derivatives derive from fluctuations in the underlying asset.

- Derivatives are usually leveraged instruments, which increases their potential risks and rewards.

- Common derivatives include futures contracts, forwards, options, and swaps.

Understanding Derivatives

A derivative is a complex type of financial security that is set between two or more parties. Traders use derivatives to access specific markets and trade different assets. The most common underlying assets for derivatives are stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates, and market indexes. Contract values depend on changes in the prices of the underlying asset.

Derivatives can be used to hedge a position, speculate on the directional movement of an underlying asset, or give leverage to holdings. These assets are commonly traded on exchanges or over-the-counter (OTC) and are purchased through brokerages. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) is among the world’s largest derivatives exchanges.

OTC-traded derivatives generally have a greater possibility of counterparty risk, which is the danger that one of the parties involved in the transaction might default. These contracts trade between two private parties and are unregulated. To hedge this risk, the investor could purchase a currency derivative to lock in a specific exchange rate. Derivatives that could be used to hedge this kind of risk include currency futures and currency swaps.

Exchange-traded derivatives are standardized and more heavily regulated than those that are traded over the counter.

Special Considerations

Derivatives were originally used to ensure balanced exchange rates for internationally traded goods. International traders needed a system to account for the differing values of national currencies.

Assume a European investor has investment accounts that are all denominated in euros (EUR). Let’s say they purchase shares of a U.S. company through a U.S. exchange using U.S. dollars (USD). This means they are now exposed to exchange rate risk while holding that stock. Exchange rate risk is the threat that the value of the euro will increase in relation to the USD. If this happens, any profits the investor realizes upon selling the stock become less valuable when they are converted into euros.

A speculator who expects the euro to appreciate compared to the dollar could profit by using a derivative that rises in value with the euro. When using derivatives to speculate on the price movement of an underlying asset, the investor does not need to have a holding or portfolio presence in the underlying asset.

Many derivative instruments are leveraged, which means a small amount of capital is required to have an interest in a large amount of value in the underlying asset.

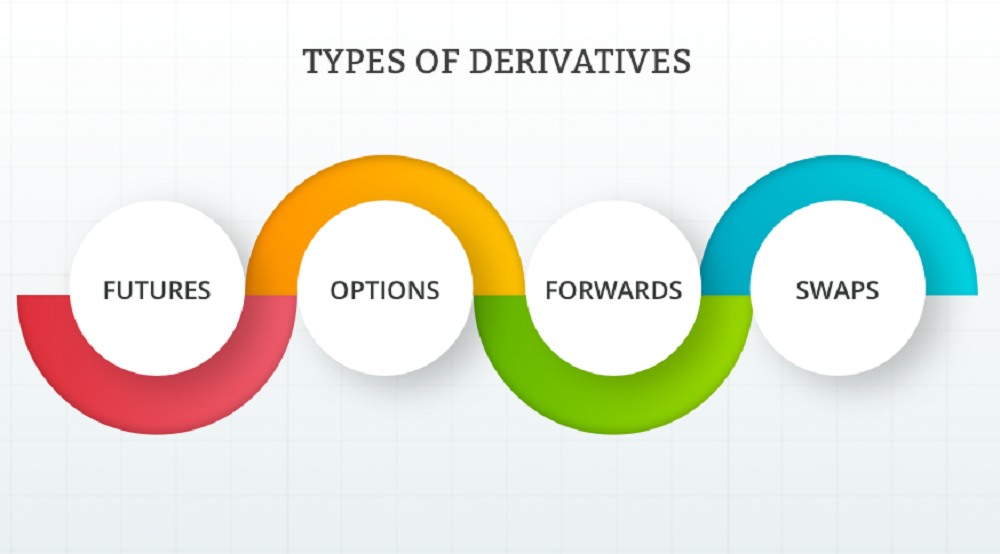

Types of Derivatives

Derivatives are now based on a wide variety of transactions and have many more uses. There are even derivatives based on weather data, such as the amount of rain or the number of sunny days in a region.

There are many different types of derivatives that can be used for risk management, speculation, and leveraging a position. The derivatives market is one that continues to grow, offering products to fit nearly any need or risk tolerance. The most common types of derivatives are futures, forwards, swaps, and options.

Futures

A futures contract, or simply futures, is an agreement between two parties for the purchase and delivery of an asset at an agreed-upon price at a future date. Futures are standardized contracts that trade on an exchange. Traders use a futures contract to hedge their risk or speculate on the price of an underlying asset. The parties involved are obligated to fulfill a commitment to buy or sell the underlying asset.

For example, say that on Nov. 6, 2021, Company A buys a futures contract for oil at a price of $62.22 per barrel that expires Dec. 19, 2021. The company does this because it needs oil in December and is concerned that the price will rise before the company needs to buy. Buying an oil futures contract hedges the company’s risk because the seller is obligated to deliver oil to Company A for $62.22 per barrel once the contract expires. Assume oil prices rise to $80 per barrel by Dec. 19, 2021. Company A can accept delivery of the oil from the seller of the futures contract, but if it no longer needs the oil, it can also sell the contract before expiration and keep the profits.

In this example, both the futures buyer and seller hedge their risk. Company A needed oil in the future and wanted to offset the risk that the price may rise in December with a long position in an oil futures contract. The seller could be an oil company concerned about falling oil prices and wanted to eliminate that risk by selling or shorting a futures contract that fixed the price it would get in December.

It is also possible that one or both of the parties are speculators with the opposite opinion about the direction of December oil. In that case, one might benefit from the contract, and one might not. Take, for example, the futures contract for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil that trades on the CME and represents 1,000 barrels of oil. If the price of oil rose from $62.22 to $80 per barrel, the trader with the long position—the buyer—in the futures contract would have profited $17,780 [($80 – $62.22) x 1,000 = $17,780]. The trader with the short position—the seller—in the contract would have a loss of $17,780.

Cash Settlements of Futures

Not all futures contracts are settled at expiration by delivering the underlying asset. If both parties in a futures contract are speculating investors or traders, it is unlikely that either of them would want to make arrangements for the delivery of several barrels of crude oil. Speculators can end their obligation to purchase or deliver the underlying commodity by closing (unwinding) their contract before expiration with an offsetting contract.

Many derivatives are in fact cash-settled, which means that the gain or loss in the trade is simply an accounting cash flow to the trader’s brokerage account. Futures contracts that are cash-settled include many interest rate futures, stock index futures, and more unusual instruments like volatility futures or weather futures.

Forwards

Forward contracts or forwards are similar to futures, but they do not trade on an exchange. These contracts only trade over-the-counter. When a forward contract is created, the buyer and seller may customize the terms, size, and settlement process. As OTC products, forward contracts carry a greater degree of counterparty risk for both parties.

Counterparty risks are a type of credit risk in that the parties may not be able to live up to the obligations outlined in the contract. If one party becomes insolvent, the other party may have no recourse and could lose the value of its position.

Once created, the parties in a forward contract can offset their position with other counterparties, which can increase the potential for counterparty risks as more traders become involved in the same contract.

Swaps

Swaps are another common type of derivative, often used to exchange one kind of cash flow with another. For example, a trader might use an interest rate swap to switch from a variable interest rate loan to a fixed interest rate loan, or vice versa.

Imagine that Company XYZ borrows $1,000,000 and pays a variable interest rate on the loan that is currently 6%. XYZ may be concerned about rising interest rates that will increase the costs of this loan or encounter a lender that is reluctant to extend more credit while the company has this variable rate risk.

Assume XYZ creates a swap with Company QRS, which is willing to exchange the payments owed on the variable-rate loan for the payments owed on a fixed-rate loan of 7%. That means that XYZ will pay 7% to QRS on its $1,000,000 principal, and QRS will pay XYZ 6% interest on the same principal. At the beginning of the swap, XYZ will just pay QRS the 1% difference between the two swap rates.

If interest rates fall so that the variable rate on the original loan is now 5%, Company XYZ will have to pay Company QRS the 2% difference on the loan. If interest rates rise to 8%, then QRS would have to pay XYZ the 1% difference between the two swap rates. Regardless of how interest rates change, the swap has achieved XYZ’s original objective of turning a variable-rate loan into a fixed-rate loan.

Swaps can also be constructed to exchange currency exchange rate risk or the risk of default on a loan or cash flows from other business activities. Swaps related to the cash flows and potential defaults of mortgage bonds are an extremely popular kind of derivative. In fact, they’ve been a bit too popular in the past. It was the counterparty risk of swaps like this that eventually spiraled into the credit crisis of 2008.

Options

An options contract is similar to a futures contract in that it is an agreement between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined future date for a specific price. The key difference between options and futures is that with an option, the buyer is not obliged to exercise their agreement to buy or sell. It is an opportunity only, not an obligation, as futures are. As with futures, options may be used to hedge or speculate on the price of the underlying asset.

In terms of timing your right to buy or sell, it depends on the “style” of option. An American option allows holders to exercise the option rights at any time before and including the day of expiration. A European option can be executed only on the day of expiration. Most stocks and exchange-traded funds have American-style options while equity indices, including the S&P 500, have European-style options.

Imagine an investor owns 100 shares of a stock worth $50 per share. They believe the stock’s value will rise in the future. However, this investor is concerned about potential risks and decides to hedge their position with an option. The investor could buy a put option that gives them the right to sell 100 shares of the underlying stock for $50 per share—known as the strike price—until a specific day in the future—known as the expiration date.

Assume the stock falls in value to $40 per share by expiration and the put option buyer decides to exercise their option and sell the stock for the original strike price of $50 per share. If the put option cost the investor $200 to purchase, then they have only lost the cost of the option because the strike price was equal to the price of the stock when they originally bought the put. A strategy like this is called a protective put because it hedges the stock’s downside risk.

Alternatively, assume an investor doesn’t own the stock currently worth $50 per share. They believe its value will rise over the next month. This investor could buy a call option that gives them the right to buy the stock for $50 before or at expiration. Assume this call option cost $200 and the stock rose to $60 before expiration. The buyer can now exercise their option and buy a stock worth $60 per share for the $50 strike price for an initial profit of $10 per share. A call option represents 100 shares, so the real profit is $1,000 less the cost of the option—the premium—and any brokerage commission fees.

In both examples, the sellers are obligated to fulfill their side of the contract if the buyers choose to exercise the contract. However, if a stock’s price is above the strike price at expiration, the put will be worthless and the seller (the option writer) gets to keep the premium as the option expires. If the stock’s price is below the strike price at expiration, the call will be worthless and the call seller will keep the premium.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Derivatives

Advantages

As the above examples illustrate, derivatives can be a useful tool for businesses and investors alike. They provide a way to do the following:

- Lock in prices

- Hedge against unfavorable movements in rates

- Mitigate risks

These pluses can often come for a limited cost.

Derivatives can also often be purchased on margin, which means traders use borrowed funds to purchase them. This makes them even less expensive.

Disadvantages

Derivatives are difficult to value because they are based on the price of another asset. The risks for OTC derivatives include counterparty risks that are difficult to predict or value. Most derivatives are also sensitive to the following:

- Changes in the amount of time to expiration

- The cost of holding the underlying asset

- Interest rates

These variables make it difficult to perfectly match the value of a derivative with the underlying asset.

Since the derivative has no intrinsic value (its value comes only from the underlying asset), it is vulnerable to market sentiment and market risk. It is possible for supply and demand factors to cause a derivative’s price and its liquidity to rise and fall, regardless of what is happening with the price of the underlying asset.

Finally, derivatives are usually leveraged instruments, and using leverage cuts both ways. While it can increase the rate of return, it also makes losses mount more quickly.

Pros

- Lock in prices

- Hedge against risk

- Can be leveraged

- Diversify portfolio

Cons

- Hard to value

- Subject to counterparty default (if OTC)

- Complex to understand

- Sensitive to supply and demand factors

What Are Derivatives?

Derivatives are securities whose value is dependent on or derived from an underlying asset. For example, an oil futures contract is a type of derivative whose value is based on the market price of oil. Derivatives have become increasingly popular in recent decades, with the total value of derivatives outstanding currently estimated at over $600 trillion.

What Are Some Examples of Derivatives?

Common examples of derivatives include futures contracts, options contracts, and credit default swaps. Beyond these, there is a vast quantity of derivative contracts tailored to meet the needs of a diverse range of counterparties. In fact, since many derivatives are traded over the counter (OTC), they can in principle be infinitely customized.

What Are the Main Benefits and Risks of Derivatives?

Derivatives can be a very convenient way to achieve financial goals. For example, a company that wants to hedge against its exposure to commodities can do so by buying or selling energy derivatives such as crude oil futures. Similarly, a company could hedge its currency risk by purchasing currency forward contracts.

Derivatives can also help investors leverage their positions, such as by buying equities through stock options rather than shares. The main drawbacks of derivatives include counterparty risk, the inherent risks of leverage, and the fact that complicated webs of derivative contracts can lead to systemic risks.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Capital Markets

What Are Capital Markets?

Capital markets are where savings and investments are channeled between suppliers—people or institutions with capital to lend or invest—and those in need. Suppliers typically include banks and investors while those who seek capital are businesses, governments, and individuals.

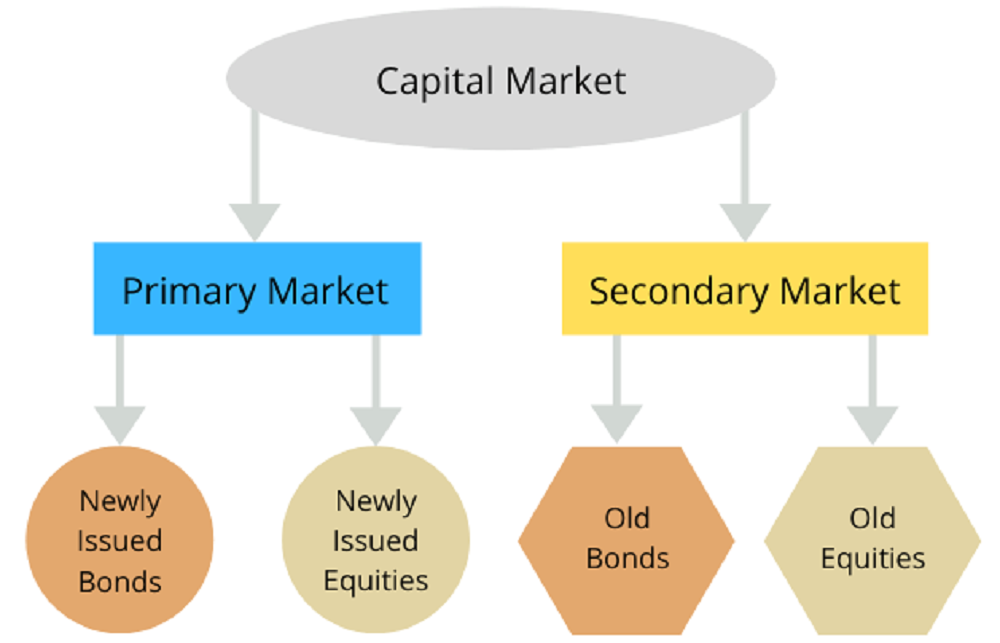

Capital markets are composed of primary and secondary markets. The most common capital markets are the stock market and the bond market.

Capital markets seek to improve transactional efficiencies. These markets bring suppliers together with those seeking capital and provide a place where they can exchange securities.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Capital markets refer to the venues where funds are exchanged between suppliers of capital and those who demand capital for use.

- Primary capital markets are where new securities are issued and sold. The secondary market is where previously issued securities are traded between investors.

- The best-known capital markets include the stock market and the bond markets.

Understanding Capital Markets

Capital market is a broad term used to describe the in-person and digital spaces in which various entities trade different types of financial instruments. These venues may include the stock market, the bond market, and the currency and foreign exchange markets. Most markets are concentrated in major financial centers such as New York, London, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

Capital markets are composed of the suppliers and users of funds. Suppliers include households—through the savings accounts they hold with banks—as well as institutions like pension and retirement funds, life insurance companies, charitable foundations, and non-financial companies that generate excess cash. The “users” of the funds distributed on capital markets include home and motor vehicle purchasers, non-financial companies, and governments financing infrastructure investment and operating expenses.

Capital markets are used primarily to sell financial products such as equities and debt securities. Equities are stocks, which are ownership shares in a company. Debt securities, such as bonds, are interest-bearing IOUs.

These markets are divided into two different categories: primary markets—where new equity stock and bond issues are sold to investors—and secondary markets, which trade existing securities. Capital markets are a crucial part of a functioning modern economy because they move money from the people who have it to those who need it for productive use.

Primary vs. Secondary Markets

Primary Market

When a company publicly sells new stocks or bonds for the first time—such as in an initial public offering (IPO)—it does so in the primary capital market. This market is sometimes called the new issues market. When investors purchase securities on the primary capital market, the company that offers the securities hires an underwriting firm to review it and create a prospectus outlining the price and other details of the securities to be issued.

All issues on the primary market are subject to strict regulation. Companies must file statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and other securities agencies and must wait until their filings are approved before they can go public.

Small investors are often unable to buy securities on the primary market because the company and its investment bankers want to sell all of the available securities in a short period of time to meet the required volume, and they must focus on marketing the sale to large investors who can buy more securities at once. Marketing the sale to investors can often include a roadshow or dog and pony show, in which investment bankers and the company’s leadership travel to meet with potential investors and convince them of the value of the security being issued.

Secondary Market

The secondary market, on the other hand, includes venues overseen by a regulatory body like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) where these previously issued securities are traded between investors. Issuing companies do not have a part in the secondary market. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Nasdaq are examples of secondary markets.

The secondary market has two different categories: the auction and the dealer markets. The auction market is home to the open outcry system where buyers and sellers congregate in one location and announce the prices at which they are willing to buy and sell their securities. The NYSE is one such example. In dealer markets, though, people trade through electronic networks. Most small investors trade through dealer markets.

Are Capital Markets the Same as Financial Markets?

While there is a great deal of overlap at times, there are some fundamental distinctions between these two terms. Financial markets encompass the broad range of venues where people and organizations exchange assets, securities, and contracts with one another, and are often secondary markets. Capital markets, on the other hand, are used primarily to raise funding, usually for a firm, to be used in operations, or for growth.

What Is a Primary vs. Secondary Market?

New capital is raised via stocks and bonds that are issued and sold to investors in the primary capital market, while traders and investors subsequently buy and sell those securities among one another on the secondary capital market but where no new capital is received by the firm.

Which Markets Do Firms Use to Raise Capital?

Companies that raise equity capital can seek private placements via angel or venture capital investors but are able to raise the largest amount through an initial public offering (IPO) when shares become listed publicly on the stock market for the first time. Debt capital can be raised through bank loans or via securities issued in the bond market.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Equity Capital Market (ECM)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is the ECM?

- Understanding ECMs

- Raising Capital in Equity Markets

- Equity Capital FAQs

What Is the Equity Capital Market (ECM)?

The equity capital market (ECM) refers to the arena where financial institutions help companies raise equity capital and where stocks are traded. It consists of the primary market for private placements, initial public offerings (IPOs), and warrants; and the secondary market, where existing shares are sold, as well as futures, options, and other listed securities are traded.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Equity Capital Markets (ECM) refers to a broad network of financial institutions, channels, and markets that together assist companies to raise capital.

- Equity capital is raised by issuing shares in the company, publicly or privately, and is used to fund the expansion of the business.

- Primary equity markets refer to raising money from private placement and mainly involves OTC markets.

- Secondary equity markets involve stock exchanges and are the primary venue for public investment in corporate equity.

- ECM activities include bringing shares to IPO and secondary offerings.

Understanding Equity Capital Markets (ECMs)

The equity capital market (ECM) is broader than just the stock market because it covers a wider range of financial instruments and activities. These include the marketing and distribution and allocation of issues, initial public offerings (IPOs), private placements, derivatives trading, and book building. The main participants in the ECM are investment banks, broker-dealers, retail investors, venture capitalists, private equity firms, and angel investors.

Together with the bond market, the ECM channels money provided by savers and depository institutions to investors. As part of the capital markets, the ECM, leads, in theory, to the efficient allocation of resources within a market economy.

Primary Equity Market

The primary equity market, where companies issue new securities, is divided into a private placement market, and a primary public market. In the private placement market, companies raise private equity through unquoted shares that are sold to investors directly. In the primary public market, private companies can go public through IPOs, and listed companies can issue new equity through seasoned issues.

Private equity firms may use both cash and debt in their investment (such as in a leveraged buyout), whereas venture capital firms typically deal only with equity investments.

Secondary Equity Market

The secondary market, where no new capital is created, is what most people typically think of as the “stock market”. It is where existing shares are bought and sold, and consists of stock exchanges and over-the-counter (OTC) markets, where a network of dealers trade stocks without an exchange acting as an intermediary.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Raising Capital in Equity Markets

Raising capital through equity markets offers several advantages for companies.

The first one is a lower debt to equity ratio. Companies will not need to access debt markets with expensive interest rates to finance future growth. Equity markets are also relatively more flexible and have a greater variety of financing options for growth as compared to debt markets. In some instances, especially in private placement, equity markets also help entrepreneurs and company founders bring in experience and oversight from senior colleagues. This will help companies expand their business to new markets and products or provide needed counsel.

But there are also problems with raising capital in equity markets. For example, the route to a public offering can be an expensive and time-consuming one. Numerous actors are involved in the process, resulting in a multiplication of costs and time required to bring a company to market.

Added to this is the constant scrutiny. While equity market investors are more tolerant of risk as compared to their debt market counterparts, they are also focused on returns. As such, investors impatient with a company that has consistently produced negative returns may abandon it, leading to a sharp drop in its valuation.

Equity Capital FAQs

What Is Equity Capital and Debt Capital?

Companies seek to raise capital in order to finance their operations and grow. Equity funding involves exchanging shares of a company’s residual ownership in return for capital. Debt funding instead relies on borrowing, where lenders are repaid principal and interest without receiving any ownership claim. In general, equity capital is more expensive and has fewer tax benefits than debt capital, but also comes with a great deal of operational freedom and less liability in the case that business fails.

How Is Equity Capital Calculated?

The equity of a company, or shareholders’ equity, is the net difference between a company’s total assets and its total liabilities. When a company has publicly-traded stock, the value of its market capitalization can be calculated as the share price times the number of shares outstanding.

What Are the Types of Equity Capital?

Equity can be categorized along several dimensions. Private equity differs from publicly-traded shares, where the former is placed via primary markets and the latter on secondary markets. Common stock is the most ubiquitous form of equity, but companies may also issue different share classes including allocations to preferred stock.

What Is the Difference Between Capital and Equity?

Capital is any resource, including cash, that a company possesses and uses for productive purposes. Equity is but one form of capital.

Financial Trading is not suitable for all investors & involved Risky. If you through with this link and trade we may earn some commission.

Bond Market

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is the Bond Market?

- Understanding Bond Markets

- History of Bond Markets

- Types of Bond Markets

- Bond Indices

- Bond Market vs. Stock Market

- Pros and Cons of the Bond Market

- Bond Market FAQs

What Is the Bond Market?

The bond market—often called the debt market, fixed-income market, or credit market—is the collective name given to all trades and issues of debt securities. Governments typically issue bonds in order to raise capital to pay down debts or fund infrastructural improvements.

Publicly traded companies issue bonds when they need to finance business expansion projects or maintain ongoing operations.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The bond market broadly describes a marketplace where investors buy debt securities that are brought to the market by either governmental entities or corporations.

- National governments generally use the proceeds from bonds to finance infrastructural improvements and pay down debts.

- Companies issue bonds to raise the capital needed to maintain operations, grow their product lines, or open new locations.

- Bonds are either issued on the primary market, which rolls out new debt, or on the secondary market, in which investors may purchase existing debt via brokers or other third parties.

- Bonds tend to be less volatile and more conservative than stock investments, but also have lower expected returns.

Understanding Bond Markets

The bond market is broadly segmented into two different silos: the primary market and the secondary market. The primary market is frequently referred to as the “new issues” market in which transactions strictly occur directly between the bond issuers and the bond buyers. In essence, the primary market yields the creation of brand-new debt securities that have not previously been offered to the public.

In the secondary market, securities that have already been sold in the primary market are then bought and sold at later dates. Investors can purchase these bonds from a broker, who acts as an intermediary between the buying and selling parties. These secondary market issues may be packaged in the form of pension funds, mutual funds, and life insurance policies—among many other product structures.

Bond investors should be mindful of the fact that junk bonds, while offering the highest returns, present the greatest risks of default.

History of Bond Markets

Bonds have been traded far longer than stocks have. In fact, loans that were assignable or transferrable to others appeared as early as ancient Mesopotamia where debts denominated in units of grain weight could be exchanged amongst debtors. In fact, recorded debt instruments history back to 2400 B.C; for instance, via a clay tablet discovered at Nippur, now present-day Iraq. This artifact records a guarantee for payment of grain and listed consequences if the debt was not repaid.1

Later, in the middle ages, governments began issuing sovereign debts in order to fund wars. In fact, the Bank of England, the world’s oldest central bank still in existence, was established to raise money to re-build the British navy in the 17th century through the issuance of bonds. The first U.S. Treasury bonds, too, were issued to help fund the military, first in the war of independence from the British crown, and again in the form of “Liberty Bonds” to help raise funds to fight World War I.

The corporate bond market is also quite old. Early chartered corporations such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Mississippi Company issued debt instruments before they issued stocks. These bonds, such as the one in the image below, were issued as “guarantees” or “sureties” and were hand-written to the bondholder.

A bond of the Dutch East India Company, dating from the 7th of November 1622, for the amount of 2400 guilders, with an annual interest of 6¼ percent. This bond was issued in Middelburg, but signed in Amsterdam.

Types of Bond Markets

The general bond market can be segmented into the following bond classifications, each with its own set of attributes.

Corporate Bonds

Companies issue corporate bonds to raise money for a sundry of reasons, such as financing current operations, expanding product lines, or opening up new manufacturing facilities. Corporate bonds usually describe longer-term debt instruments that provide a maturity of at least one year.

Corporate bonds are typically classified as either investment-grade or else high-yield (or “junk”). This categorization is based on the credit rating assigned to the bond and its issuer. An investment-grade is a rating that signifies a high-quality bond that presents a relatively low risk of default. Bond-rating firms like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s use different designations, consisting of the upper- and lower-case letters “A” and “B,” to identify a bond’s credit quality rating.

Junk bonds are bonds that carry a higher risk of default than most bonds issued by corporations and governments. A bond is a debt or promise to pay investors interest payments along with the return of invested principal in exchange for buying the bond. Junk bonds represent bonds issued by companies that are financially struggling and have a high risk of defaulting or not paying their interest payments or repaying the principal to investors. Junk bonds are also called high-yield bonds since the higher yield is needed to help offset any risk of default. These bonds have credit ratings below BBB- from S&P, or below Baa3 from Moody’s.

Government Bonds

National-issued government bonds (or sovereign bonds) entice buyers by paying out the face value listed on the bond certificate, on the agreed maturity date, while also issuing periodic interest payments along the way. This characteristic makes government bonds attractive to conservative investors. Because sovereign debt is backed by a government that can tax its citizens or print money to cover the payments, these are considered the least risky type of bonds, in general.

In the U.S., government bonds are known as Treasuries, and are by far the most active and liquid bond market today. A Treasury Bill (T-Bill) is a short-term U.S. government debt obligation backed by the Treasury Department with a maturity of one year or less. A Treasury note (T-note) is a marketable U.S. government debt security with a fixed interest rate and a maturity between one and 10 years. Treasury bonds (T-bonds) are government debt securities issued by the U.S. Federal government that have maturities greater than 20 years.

Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds—commonly abbreviated as “muni” bonds—are locally issued by states, cities, special-purpose districts, public utility districts, school districts, publicly-owned airports and seaports, and other government-owned entities who seek to raise cash to fund various projects.